Untangling History: The Relationship Between Events

Understanding history involves more than memorizing a timeline; it demands a critical analysis of the relationship between events. The discipline of historiography provides methodologies for this analysis. The Annales School, for instance, emphasizes long-term social structures to understand how these shape specific occurrences. Furthermore, the concept of historical causation explores the nuanced web of factors leading to outcomes. Considering all of these entities within the framework of understanding the past is critical for relationship between events. Wikipedia, as an expansive repository, provides a starting point for exploring these connections, but it is crucial to critically evaluate the information and cross-reference it with scholarly sources.

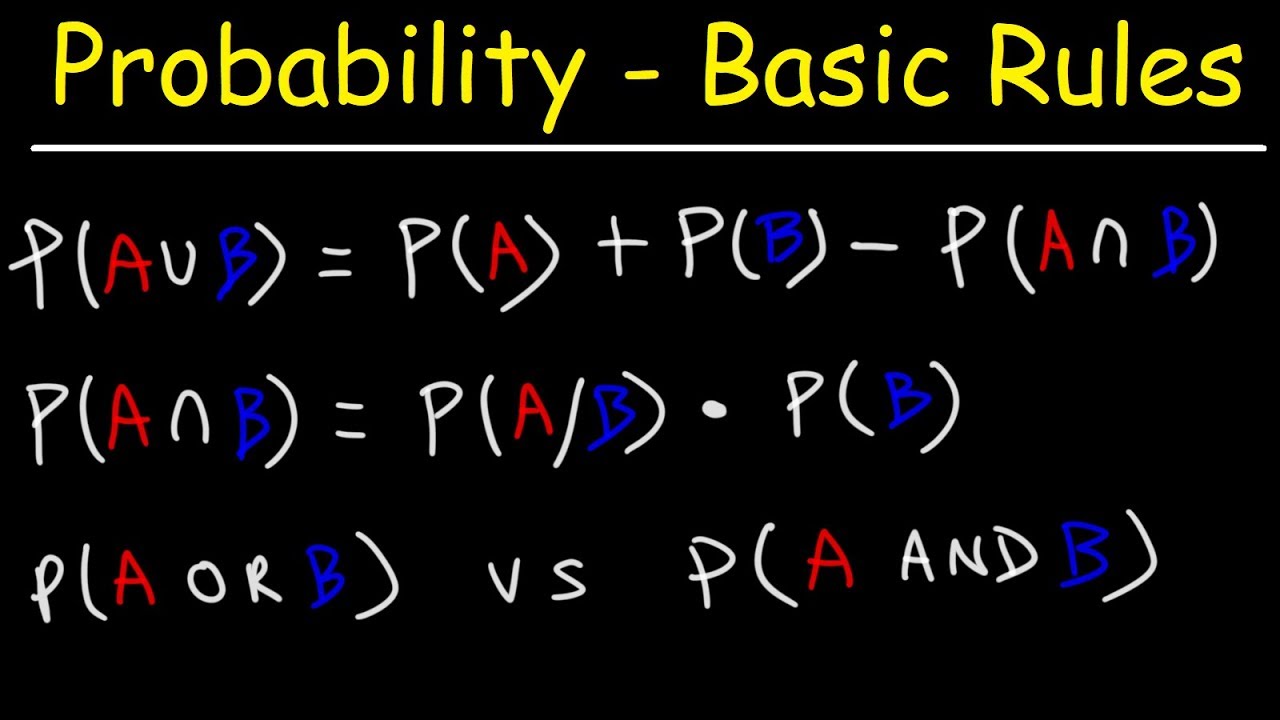

Image taken from the YouTube channel The Organic Chemistry Tutor , from the video titled Multiplication & Addition Rule - Probability - Mutually Exclusive & Independent Events .

Unveiling the Interconnected Tapestry of History

History is not a collection of isolated incidents, but rather a complex web of interconnected events. Understanding these intricate connections is crucial for comprehending the past and its enduring influence on the present. Approaching history with a simplistic lens risks distorting the truth and perpetuating inaccurate narratives.

Therefore, a nuanced analysis that acknowledges the multifaceted nature of historical processes is essential.

The Danger of Oversimplification

Reducing history to a series of easily digestible sound bites can be tempting, especially in an era of instant information. However, this approach often obscures the underlying complexities and nuances that shape historical developments. Oversimplification can lead to:

- Misunderstanding of motivations: Attributing complex actions to single causes ignores the myriad factors influencing human behavior.

- Ignoring unintended consequences: Focusing solely on intended outcomes neglects the often-unforeseen repercussions of historical events.

- Perpetuating harmful stereotypes: Simplifying historical narratives can reinforce prejudiced views and distort the experiences of marginalized groups.

The Need for Nuanced Analysis

To truly understand history, we must move beyond simplistic explanations and embrace a more nuanced approach. This involves:

- Examining multiple perspectives: Acknowledging that different individuals and groups may have varying interpretations of the same events.

- Considering the broader context: Placing events within their social, economic, political, and cultural frameworks.

- Recognizing the role of contingency: Accepting that history is not predetermined and that outcomes could have been different.

Thesis Statement

A thorough understanding of history requires analyzing the causality, correlation, and historical context of events.

All the while, it is critical to acknowledge bias and diverse interpretations to avoid simplistic narratives. This approach allows us to move beyond superficial understandings and delve into the rich tapestry of the past.

Unraveling the interconnected tapestry of history requires a meticulous approach, one that moves beyond superficial observations to examine the deeper relationships between events. We must acknowledge the intricate dance between cause and effect, recognizing that historical occurrences are rarely isolated incidents but rather part of a complex chain of actions and consequences.

Deciphering the Code: Causality vs. Correlation

At the heart of historical analysis lies the critical task of distinguishing between causality and correlation. These two concepts, while often intertwined, represent fundamentally different relationships between events. Grasping this distinction is paramount for constructing accurate and insightful historical narratives. Failing to do so can lead to flawed interpretations and a distorted understanding of the past.

Understanding Causality

Causality refers to a relationship where one event directly causes another. In other words, event A is said to cause event B if A is directly responsible for B occurring. Establishing causality requires demonstrating a direct link between the cause and the effect. It is not enough to simply observe that two events occurred in sequence.

To establish causality, one must demonstrate:

- Temporal precedence: The cause must precede the effect in time.

- Covariation: The cause and effect must occur together; when the cause is present, the effect is likely to occur, and when the cause is absent, the effect is less likely to occur.

- Elimination of alternative explanations: Other potential causes must be ruled out.

Causality is the bedrock upon which we can build theories about why something happened.

Exploring Correlation

Correlation, on the other hand, indicates a statistical association between two or more variables. This means that the variables tend to move together, either in the same direction (positive correlation) or in opposite directions (negative correlation). However, correlation does not imply causation.

Just because two events are correlated does not mean that one caused the other. They might both be influenced by a third, unobserved variable, or the correlation might be purely coincidental.

Common examples include:

- Ice cream sales and crime rates tending to rise together during the summer (both are influenced by warmer weather).

- The decline in the number of pirates correlating with global warming.

It is crucial to recognize that correlation can be a valuable starting point for investigation, but it should never be mistaken for proof of a causal relationship.

The Perils of Confusing Correlation with Causality

The confusion between correlation and causality can lead to serious misinterpretations of history. Attributing cause-and-effect relationships based solely on observed correlations can result in:

- Misguided policy decisions: Interventions based on faulty causal assumptions are likely to be ineffective or even counterproductive.

- Inaccurate historical narratives: Distorted accounts of the past can perpetuate harmful stereotypes and hinder our ability to learn from history.

- A superficial understanding of complex events: Oversimplifying historical processes by attributing them to single, easily identifiable causes obscures the underlying complexities and nuances.

For instance, consider the rise of nationalism in 19th-century Europe and the growth of industrialization. While these two phenomena were correlated, it would be simplistic to argue that industrialization directly caused nationalism. Instead, both were influenced by a complex interplay of factors, including economic changes, social transformations, and intellectual developments.

Similarly, the correlation between economic inequality and social unrest does not automatically imply that inequality causes unrest. Other factors, such as political oppression, cultural grievances, and the presence of charismatic leaders, may also play significant roles.

The key is to rigorously analyze the evidence, consider alternative explanations, and avoid jumping to conclusions based solely on observed correlations.

Unraveling the interconnected tapestry of history requires a meticulous approach, one that moves beyond superficial observations to examine the deeper relationships between events. We must acknowledge the intricate dance between cause and effect, recognizing that historical occurrences are rarely isolated incidents but rather part of a complex chain of actions and consequences.

Deciphering the code of causality and correlation arms us with vital tools, but these are most effective when applied within a broader framework. Like detectives piecing together a puzzle, historians must consider the environment in which events unfold to truly understand their meaning.

Framing the Picture: The Significance of Historical Context

Historical context serves as the backdrop against which events play out, imbuing them with meaning and significance.

It is the lens through which we can view the past, allowing us to understand not just what happened, but why it happened in the way it did. Without context, even seemingly straightforward events can become distorted, leading to inaccurate or incomplete understandings of the past.

The Indispensable Role of Context

Placing events within their historical context is not merely an optional exercise; it is an essential component of responsible historical analysis.

It allows us to move beyond surface-level narratives and delve into the complex web of circumstances that shaped the actions, motivations, and consequences of historical actors.

Without understanding the social, economic, political, and cultural landscape of a particular time and place, we risk imposing our own modern values and biases onto the past, resulting in fundamental misinterpretations.

Weaving the Tapestry of Context: Key Contributing Factors

Historical context is not a monolithic entity; rather, it is a multifaceted construct composed of various interconnected factors.

Social context encompasses the prevailing social norms, values, hierarchies, and relationships that governed people's lives.

Economic context refers to the economic systems, resources, and structures that shaped production, distribution, and consumption.

Political context includes the forms of government, power structures, ideologies, and conflicts that influenced decision-making and governance.

Cultural context encompasses the shared beliefs, values, traditions, artistic expressions, and intellectual currents that defined a society's worldview.

These factors are not mutually exclusive; they interact and influence each other in complex ways, shaping the overall historical context in which events unfold.

Distorting the Image: The Perils of Neglecting Context

Neglecting historical context can have profound consequences, leading to distorted interpretations of historical actions and motivations.

Consider, for example, judging historical figures by contemporary moral standards without acknowledging the different ethical frameworks that prevailed in their time.

What might seem abhorrent today may have been considered acceptable, or even virtuous, in a different era. Similarly, without understanding the economic realities of a particular time, we may misinterpret the decisions and actions of individuals and groups struggling to survive within those constraints.

By failing to consider the historical context, we risk imposing our own biases and values onto the past, creating a distorted and inaccurate representation of historical events.

Weaving together the threads of causality, correlation, and historical context provides a richer tapestry of understanding, but the picture remains incomplete without acknowledging the subjective element inherent in historical inquiry. Every source, every narrative, every interpretation is filtered through a lens, colored by the perspectives and agendas of its creator.

Through the Looking Glass: Bias, Interpretation, and Historiography

History, as it's often said, is written by the victors. But even when penned by the seemingly neutral, the human element invariably introduces bias. Recognizing this inherent subjectivity is not an admission of history's unreliability, but rather a crucial step towards a more nuanced and responsible understanding of the past.

The Inevitable Presence of Bias

Bias manifests in countless forms, from the conscious omission of inconvenient facts to the subtle framing of events to support a particular viewpoint.

It can stem from nationalistic pride, religious conviction, political allegiance, or simply the limitations of one's own lived experience.

Historical sources, whether they be official documents, personal letters, or eyewitness accounts, are products of their time and reflect the prevailing social, cultural, and intellectual currents.

Acknowledging the presence of bias requires a critical approach to source material, questioning the motives and perspectives of the author, and seeking out alternative accounts to gain a more balanced understanding.

The Kaleidoscope of Interpretations

The same historical events can be interpreted in radically different ways, depending on the interpreter's own background, values, and objectives.

What one historian might see as a heroic struggle for freedom, another might portray as a descent into anarchy.

These differing interpretations are not necessarily evidence of falsehood or distortion, but rather reflections of the complex and multifaceted nature of the past.

Understanding the factors that shape these divergent perspectives is essential for avoiding simplistic judgments and appreciating the richness and complexity of historical debate.

The Guiding Hand of Historiography

Historiography, the study of how history is written, provides a framework for understanding the evolution of historical interpretations over time.

It examines the methods, assumptions, and intellectual contexts that have shaped the work of historians, revealing how their own biases and agendas have influenced their narratives.

By studying historiography, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the intellectual and cultural forces that have shaped our understanding of the past, and become more aware of the limitations of our own perspectives.

This is essential for responsible historical analysis.

Mitigating Bias Through Critical Analysis

While bias can never be entirely eliminated, its effects can be mitigated through rigorous critical analysis.

This involves carefully evaluating the credibility and reliability of sources, comparing different accounts of the same events, and considering the broader historical context in which those events unfolded.

Questioning assumptions, challenging conventional wisdom, and seeking out diverse perspectives are all essential components of this process.

By embracing a spirit of intellectual humility and open-mindedness, we can move closer to a more accurate and nuanced understanding of the past.

Weaving together the threads of causality, correlation, and historical context provides a richer tapestry of understanding, but the picture remains incomplete without acknowledging the subjective element inherent in historical inquiry. Every source, every narrative, every interpretation is filtered through a lens, colored by the perspectives and agendas of its creator.

Case Studies: Unraveling Interconnectedness in Action

To truly appreciate the multifaceted nature of historical analysis, it's essential to move beyond abstract concepts and examine specific events through the lenses of causality, correlation, historical context, and diverse interpretations. By delving into in-depth case studies, we can witness the interplay of these factors and gain a more nuanced understanding of the past.

Let's consider a few significant historical turning points: World War I, the French Revolution, and the Cold War. Each of these events offers a unique opportunity to explore the complexities of historical analysis and the challenges of constructing accurate and comprehensive narratives.

World War I: A Tangled Web of Causation

World War I serves as a stark example of how a complex chain of events, fueled by a potent mix of nationalism, imperialism, and militarism, can lead to global conflict.

While the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand is often cited as the immediate trigger, it's crucial to recognize that this event was merely the spark that ignited a powder keg of underlying tensions.

The intricate web of alliances, the arms race between major European powers, and the competing colonial ambitions all played significant roles in creating a climate of instability and suspicion.

Understanding the intricate interplay of these factors is essential for grasping the true causes of World War I. Analyzing the long-term and short-term causes, the role of individual actors, and the impact of technological advancements provides a more complete picture of this devastating conflict.

The French Revolution: Interpretations in Conflict

The French Revolution, a period of radical social and political upheaval in late 18th-century France, continues to captivate and divide historians.

Analyzing the social, economic, and political factors that contributed to the revolution requires careful consideration of different interpretations of its causes and consequences. Was it primarily a bourgeois revolution, driven by the rising merchant class? Or was it a popular uprising, fueled by the suffering of the peasantry and the urban poor?

Examining primary sources, such as the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and accounts from those who lived through the terror, offers valuable insights into the diverse perspectives and experiences of the era.

However, even these primary sources must be approached critically, recognizing that they, too, are products of their time and reflect the biases of their creators. The French Revolution showcases a variety of conflicting views and ideologies that still generate debate among historians.

Analyzing the revolution with multiple perspectives is a way to paint a more comprehensive picture of it.

The Cold War: Ideology, Geopolitics, and Competing Narratives

The Cold War, a decades-long ideological and geopolitical struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union, profoundly shaped the 20th century.

Understanding this conflict requires careful consideration of the historical context, including the legacy of World War II, the rise of nuclear weapons, and the spread of communism.

Geopolitical factors, such as the division of Europe and the competition for influence in the developing world, also played a crucial role.

However, the Cold War was not simply a clash of power; it was also a battle of ideas, with each side promoting its own vision of the ideal society.

Examining the competing narratives of the Cold War, as presented by both the United States and the Soviet Union, reveals the power of ideology in shaping perceptions and justifying actions.

Creating a timeline of the Cold War's major events from the end of World War II to the collapse of the Soviet Union, is essential for understanding the evolving dynamics of the conflict. Analyzing primary sources from both sides, along with the accounts of those who lived through the era, provides a nuanced understanding of this defining period.

Weaving together the threads of causality, correlation, and historical context provides a richer tapestry of understanding, but the picture remains incomplete without acknowledging the subjective element inherent in historical inquiry. Every source, every narrative, every interpretation is filtered through a lens, colored by the perspectives and agendas of its creator.

Therefore, effectively navigating the world of historical research requires a reliable toolkit – a collection of resources and methodologies that empower us to dissect, analyze, and interpret the past with accuracy and insight. These tools help us move beyond simply knowing what happened, to understanding why it happened and what it meant.

Tools of the Trade: Essential Resources for Historical Analysis

Historical analysis is akin to detective work: assembling clues, evaluating evidence, and constructing a coherent narrative. But unlike a crime scene, the historical record is often incomplete, fragmented, and subject to multiple interpretations. To navigate this complex terrain, historians rely on a range of essential resources, each with its own strengths and limitations.

Primary Sources: Direct Windows to the Past

Primary sources are the bedrock of historical research. They are original materials created during the time period under investigation, offering direct, firsthand accounts of events, ideas, and experiences.

These can take many forms:

- Documents: Letters, diaries, official records, treaties, laws, newspapers, pamphlets.

- Artifacts: Tools, clothing, buildings, artwork, everyday objects.

- Creative Works: Literature, music, visual arts.

- Oral Histories: Interviews, testimonies, recorded recollections.

Analyzing primary sources involves careful scrutiny and critical evaluation.

One must consider the author's perspective, intended audience, purpose, and potential biases. What does the source reveal explicitly? What does it imply or omit? What can we infer about the social, cultural, and political context in which it was created?

By grappling with these questions, we can unlock valuable insights into the past and avoid simply accepting information at face value.

Secondary Sources: Navigating the Existing Scholarship

Secondary sources provide interpretations and analyses of primary sources. They are works created after the event or period being studied, often by historians or other scholars.

These include:

- Books: Monographs, biographies, edited collections.

- Articles: Journal articles, essays.

- Documentaries: Films that analyze historical events.

Secondary sources are essential for understanding the existing scholarship on a topic, identifying different perspectives, and developing our own interpretations.

They provide a framework for research, help us identify relevant primary sources, and offer valuable context for understanding complex events.

However, it's crucial to approach secondary sources with a critical eye. Historians, like all writers, have their own biases, agendas, and interpretations. It's important to compare different secondary sources, identify areas of agreement and disagreement, and evaluate the evidence and arguments presented. By engaging with the existing scholarship critically, we can develop a more nuanced and informed understanding of the past.

The Timeline: Charting the Course of History

A timeline is a visual representation of events in chronological order. It serves as a fundamental tool for organizing information, identifying patterns, and understanding the sequence of events.

Timelines can be simple or complex, depending on the scope of the study. They can be used to track the development of a particular event, the evolution of an idea, or the course of a historical period.

Creating a timeline involves identifying key events, determining their dates, and arranging them in chronological order. This process can reveal important relationships between events, highlight turning points, and identify gaps in our knowledge.

Furthermore, timelines can be used to visualize the duration of events, compare the timing of different developments, and identify periods of rapid change or relative stability. By providing a clear and concise overview of the historical landscape, timelines can help us make sense of complex events and develop a deeper appreciation for the flow of history.

Video: Untangling History: The Relationship Between Events

Untangling History: FAQs

Understanding how historical events connect can be tricky. Here are some frequently asked questions to help clarify the relationship between events and how to better understand them.

What does "relationship between events" really mean in historical analysis?

It refers to how one event influences or is influenced by another. This includes cause and effect, but also broader connections like shared origins, similar outcomes, or how one event enables another. Recognizing these relationships is crucial for a deeper historical understanding.

Why is understanding the relationship between events important?

Understanding these relationships helps avoid simplistic narratives. It allows us to see the complexities and nuances of history, moving beyond simple cause-and-effect to understand multiple factors and long-term consequences. This leads to a more accurate and nuanced understanding of the past.

How do historians determine the relationship between events?

Historians use primary and secondary sources to analyze the evidence. They look for patterns, correlations, and direct connections documented in letters, diaries, official records, and other historical materials. Careful analysis and interpretation is key to establishing a verifiable relationship between events.

What are some common mistakes people make when analyzing the relationship between events?

One common error is assuming correlation equals causation. Just because two events occur close together doesn't mean one caused the other. Another is ignoring other contributing factors or only focusing on one cause. A comprehensive understanding requires looking at multiple influences that shape the relationship between events.